The Disinfodemic Has Hit Eastern Europe

August 14, 2020 in UncategorizedThe number of requests for information about COVID-19 developments, such as death tolls and vaccine updates, remains high. Some are taking advantage of the current desire for information as evidenced by the rising spread of misinformation and disinformation about the virus. First of all, it is important to distinguish between the two. While misinformation is defined as false information that is spread, regardless of intent to mislead, disinformation generally refers to deliberately misleading or biased information and manipulated narrative or facts. The crucial difference between the two, therefore, is intent.

Disinformation is dangerous as it can be destructive and divisive. It has often been used by countries to undermine rival nations. Since the pandemic started we have seen several incidents involving spread of disinformation. Cyber-security firm FireEye warned in a July 2020 report, “’Ghostwriter’ Influence Campaign: Unknown Actors Leverage Website Compromises and Fabricated Content to Push Narratives Aligned with Russian Security Interests”, that hackers have broken into news websites and posted fake stories aiming at stirring up anti-NATO sentiment. FireEye researchers said these are designed to “chip away” at support for NATO in the eastern European countries of Poland and Lithuania, in addition to Latvia. According to them, this disinformation campaign, which has been dubbed Ghostwriter, has been going on since 2017.

While the people behind the attacks have not been identified, the stories are “aligned with Russian security interests” according to the researchers. They generally attempt to discredit NATO and the US, and include discussion favouring Russia. Furthermore, “[i]t appears, based on the limited public information available regarding the website compromises we have tied to Ghostwriter, that the actors behind the campaign are relatively well-resourced, either directly possessing traditional cyber threat capabilities themselves or having ready access to operational support from others who do.”

The hackers publish “falsified news articles, quotes, correspondence and other documents designed to appear as coming from military officials and political figures in the target countries.” For instance, in April 2020 a fake message calling for troops to fight against “the American occupation” was published on the Polish War Studies Academy’s website. It claimed to be from this organisation’s commander and came after Poland had begun seeking to have the US establish a permanent military base there. Meanwhile Russia has called the arrival of US troops there a threat to its security. On May 27, a falsified interview transcript containing quotes from US Army Lt. Gen. Cavoli was published. Its narrative was that Cavoli criticised Polish and Baltic militaries.

More recently, several fake news articles have been focused on the current pandemic, with some suggesting that NATO is pulling out of Lithuania because of the COVID-19 virus and others blaming NATO forces in Europe of contributing to its spread. For instance, in March 2020, falsified quotes from Lithuanian Defence Minister Ramundas Karoblis was published which contained statements that Lithuania would go ahead with DEFENDER-Europe 20 NATO Exercises despite the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to these, FireEye identified several other individual attacks and collected it into what they say is a “broader influence campaign.”

The hackers apparently gained access to the targeted websites’ content management systems (CMS) to replace old articles with own content or post completely new false articles. “Website content management system vulnerabilities are commonplace and easily exploited,” Mallory Knodel, CTO at the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), said. “Strong and secure websites protect against this by making only cached versions of the website available to users through content delivery networks, and some might go so far as to ensure that the back end, the site’s CMS, [isn’t] exposed on the internet at all, and that version control for static page content, like the content of a news story, is closely monitored.” Knodel continued: “Strong authentication for anyone with back-end access is a must, and this can be done through the use of strong passwords, second-factor authentication, and limiting access to those on a virtual private network.”

Furthermore, director of security strategy at Akamai, Tony Lauro, warned that CMSs may be even easier to compromise when attackers can leverage security weaknesses created by the current pandemic-related remote working conditions. “If an attacker can gain access to [the] CMS platform, either by taking over the remote employee’s workstation or by otherwise phishing their login credentials, as you’d imagine, they’d have the keys to the kingdom,” said Lauro. Lauro suggests that “[o]rganizations should look into zero trust-related technologies for remote access so that when employees connect to internal content management systems to upload media, they are not connecting to any additional network resources. This is done by way of a proxied connection between the inside resources and outside users.”

To combat disinformation, independent fact-checking organisations; news organisations; platforms; academics; and civil society organisations continuously monitor and fact-check published information. For instance, an International Fact Checking Network (IFCN) initiative currently spanning 70+ countries fact-checked and debunked over 1.500 COVID-19 related online falsehoods. Such initiatives are vital to uncover the continuously changing disinformation. Other measures have included criminalising acts of producing or sharing COVID-19 disinformation. For instance, Serbia announced a decree in April 2020 limiting access to public information, for which the stated goal was to limit the spread of fake news. On March 31 Russian lawmakers passed amendments to Article 207 of Criminal Code, under which those found to have deliberately spread false information about serious matters of public safety, such as COVID 19, will face fines of up to €23,000 and up to five years in prison. Such measures have however been criticised for having a potential chilling effect on journalists writing about the pandemic as they can stifle independent reporting on the government’s measures. While examining the validity of this criticism is beyond this article, it is important to note that there may be other motivations behind measures implemented to combat disinformation.

Criticism aside, measures must be implemented to combat the current disinfodemic, and not just in eastern Europe as the campaign may eventually spread beyond this region. FireEye warned that the Ghostwriter campaign could be repurposed and target other geographies. “Given the established history of cyber threat and information operations tactics regularly migrating from targeting Eastern Europe to targeting Western Europe and the U.S., this campaign may warrant special attention, especially as elections near,” they said. It is therefore important that security firms and governments continue to pay attention to this campaign and any future developments.

Access to truthful information is essential during the current crisis. Reliable information is necessary for individuals to adapt their behaviour, such as implementing certain social distancing measures, and for countries to learn from other countries’ experiences and responses. Disinformation can be deadly as it sows confusion about live-saving personal and policy choices. It is therefore vital that security for news websites is prioritised and that published information is properly monitored and fact-checked.

Neo-Nazi’s Infiltration within Germany’s Police and Military

August 14, 2020 in UncategorizedLast month, Germany’s defense minister, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, disbanded a fighting company within the KSK, one of the most elite military units in Germany due to the growing of Neo-Nazi views among the members. It was discovered in May that one of the members of the KSK, a sergeant major with the nickname of “Little Sheep”, was hoarding weapons in his house. German authorities found various weapons buried in his garden such as two kilograms of PETN plastic explosives, a detonator, a fuse, an AK-47, a silencer, two knives, a crossbow, and thousands of rounds of ammunition. They also found numerous Nazi memorabilia such as an SS songbook and 14 editions of a magazine for former members of the Waffen SS. The weapons were believed to be stolen from the German military. German officials stated that 48,000 rounds of ammunition and 62 kilograms of explosives have disappeared from the KSK alone, not the whole German military. Politicians in Germany have been in denial regarding the issue of far-rights threats within the military and the police. Weapons have been disappearing from military stockpiled without being investigated. Now, the government seems to have accepted the ugly truth and try to act on it, since cases of far-right extremists in the military and the police, some hoarding weapons and Nazi memorabilia, have multiplied drastically. The mind-set of seeing this as individual cases seems to be not making sense anymore as the numbers indicated that this phenomenon could be well organized. A Counter-intelligence unit within Germany’s military has conducted an investigation towards more than 600 soldiers for suspicion of holding far-right views.

Not only within the military, the Neo-Nazi infiltration within the police force is also concerning. For instance, there was a case in Northern Germany when a police detective started a far-right group chat that listed a list which consisted of thousands of names including politicians, journalists, and activists considered to be the enemy of the Neo-Nazi movement that must be eliminated. The authorities also found more than 50,000 rounds of ammunition hoarded by the police detective inside his apartment along with several guns and flash grenades. The detective stated that the Neo-Nazi group was filled with many police and soldiers. Another case that Germany should pay attention to is the fact that swastika graffiti and anti-Islam slogans are a regular feature in many police academies in Germany. It is also well known that the police never acted seriously in regards to cases involving Neo-Nazi, Anti-Semitism, and racism. The most well-known example of such behavior was the killing spree carried out by the self-named National Socialist Underground (NSU). Between the years 2000 and 2007, the right-wing extremist terror cell murdered nine business owners with immigrant backgrounds, as well as a female police officer. Within this case, the police focused their suspicion towards the victim’s families rather than looking for racist motives. Eventually, the murder spree was ended by the suicide of the perpetrators, a huge failure for the police due to the ignorance towards Neo-Nazi issues.

In general, Far-Right problems in Germany have been a problem for quite a long time, even infiltrated the police and military force. The problem worsens with the emergence of AFD, a Far-Right political party that legitimized the ideology under the pretext of countering the issue of foreign immigrants. The massive number of cases in regards to police and military members exposed in Neo-Nazi views, stealing weapons from the state stockpiles, created a community for like-minded people, could be seen as a signed that the whole movement is organized, thus having a plan which could endangered freedom and democracy in Germany. The government of Germany has to take the issue much more seriously to prevent the ugly past to be repeated.

Media Reports: Lebanese Prime Minister To Resign as Government Falls

August 10, 2020 in UncategorizedLocal Lebanese media reported on Monday 10 August that Lebanese Prime Minister Hassan Diab is set to resign within hours after the entire government stepped down. This comes as anti-government protesters continue to demand political change after last week’s explosion in Beirut, which killed more than 160 people and injured around 6,000.

The 4 August port warehouse detonation of more than 2,000 tonnes of ammonium nitrate destroyed a swathe of the Mediterranean city, compounding months of political and economic turmoil. Sources have indicated that the cabinet, which was formed back in January, was due to meet on Monday, with a number of ministers wanting to resign. The information and environment ministers resigned on Sunday, along with several lawmakers. On Monday, state-run National News Agency reported, citing the conduct of the government in the aftermath of last week’s blast, that Justice Minister Marie Claude Najm had reassigned earlier in the day.

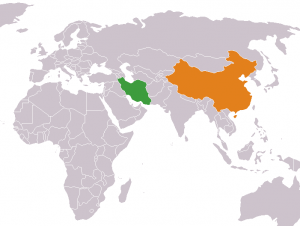

Iran’s Lifeline and China’s Foothold: Examining the possible implications of the pending Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership

August 7, 2020 in China, Iran, United States On 11 July 2020, the Iranian government was reported to have approved a draft 25-year deal with China on economic, military and security cooperation. Titled the “Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership”, Iranian officials have publicly stated that there is a pending agreement with China. A copy of the leaked 18-page document has been obtained by The New York Times labelled “final version” and dated June 2020. One Iranian official and several others who have discussed the agreement with the Iranian government have confirmed that it is the actual document waiting to be submitted to the Iranian parliament for approval. In China, officials have not disclosed the terms of the agreement and it is not clear whether Beijing has approved the deal . In the opening sentence of the document it states: “two ancient Asian cultures, two partners in the sectors of trade, economy, politics, culture and security with a similar outlook and many mutual bilateral and multilateral interests will consider one another strategic partners”. This Sino-Iranian pact throws Iran an economic lifeline at time as its economy is under severe pressure from United States sanctions. The pact also paves the way for Chinese influence to extend into the Middle East. The agreement may create further tension between Washington and Beijing, who are currently engaged in a trade war.

On 11 July 2020, the Iranian government was reported to have approved a draft 25-year deal with China on economic, military and security cooperation. Titled the “Sino-Iranian Comprehensive Strategic Partnership”, Iranian officials have publicly stated that there is a pending agreement with China. A copy of the leaked 18-page document has been obtained by The New York Times labelled “final version” and dated June 2020. One Iranian official and several others who have discussed the agreement with the Iranian government have confirmed that it is the actual document waiting to be submitted to the Iranian parliament for approval. In China, officials have not disclosed the terms of the agreement and it is not clear whether Beijing has approved the deal . In the opening sentence of the document it states: “two ancient Asian cultures, two partners in the sectors of trade, economy, politics, culture and security with a similar outlook and many mutual bilateral and multilateral interests will consider one another strategic partners”. This Sino-Iranian pact throws Iran an economic lifeline at time as its economy is under severe pressure from United States sanctions. The pact also paves the way for Chinese influence to extend into the Middle East. The agreement may create further tension between Washington and Beijing, who are currently engaged in a trade war.

Components of the Partnership

The draft agreement, first proposed by Chinese president Xi Jinping in a visit to Iran in 2016, allows for 400 billion US dollars’ worth of Chinese investment in Iran in exchange for heavily discounted oil. China aims to invest in various sectors in Iran including oil and gas, telecommunications, banking, cyber security and transportation. Nearly 100 projects are cited in the deal including the construction of airports, high-speed railways and subways. Moreover, the deal proposes the development of free-trade zones in Maku, located in north-western Iran; in Abadan, where the Shatt al-Arab river flows into the Persian Gulf and on the Gulf island of Qeshm. The draft also proposes Chinese access to Jask, a major Iranian port located just outside the strait of Hormuz, the entrance to the Persian Gulf. The strait is a strategically important choke point through which one third of the worlds liquefied natural gas and a quarter of the world’s oil pass. China will also build the infrastructure for 5G telecommunications network in Iran in addition to offering the new Chinese Global Positioning System to help the Iranian government in asserting greater control over cyberspace. The draft agreement describes deepening military and security ties, calling for joint military exercises, joint research and weapons development in addition to intelligence sharing. This military and security cooperation, according to the draft, will be in place to fight the “lopsided battle with terrorism, drug and human trafficking and cross border crimes”. The draft also allows for 5000 Chinese security personnel in Iran to protect Chinese projects.

Benefits to Iran

If implemented, the agreement gives Iran a critical lifeline. US president Donald Trump has been waging a maximum pressure campaign on Iran’s economy since 2018. Trump’s administration has threatened to sanction countries in Europe and elsewhere who buy oil and other exports from Iran. Trump said the campaign was aimed at eliminating the threat of Tehran’s ballistic missile program, to halt its terrorist activities around the world and to stop its “menacing activity across the Middle East”. Although Trump’s campaign against Iran has not achieved these objectives, it has pushed Iran deep into recession. Iran’s economy was expected to contract by 7.1 percent in 2019 according to the United Nations and by 9.5 percent according to the International Monetary Fund. The IMF estimated that Iran’s reserves of foreign currency have been reduced to 86 billion, 20 percent below their level in 2013. Oil exports have plunged since the US began imposing sanctions again in 2018. The COVID-19 outbreak, the worst in the Middle East, and rising tensions with the US have put further strain on Iran. Thus, the agreement alleviates a great amount of economic hardship from the Islamic republic.

Benefits to China

The most obvious advantage this agreement provides for China is discounted oil. China obtains 75 percent of its oil from abroad and is currently the world’s largest importer of the natural resource at 10 million barrels a day. Iran also provides an additional terrestrial route for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the ambitious global infrastructure development strategy Beijing adopted in 2013. However, trade with Iran has not been a priority for Beijing in recent years. China invested less than 27 billion dollars in Iran from 2005 to 2019. Annual investments have dropped every year since 2016. In fact, China has invested significantly more in Arab Gulf countries compared to Chinese investments in Iran. Furthermore, for years China has mostly abided by US sanctions showing that Beijing prioritised trade with the US over ties with Iran. This particular agreement between Tehran and Beijing was proposed only after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was signed. The JCPOA is an agreement between Iran and major powers including the US to limit Iran’s nuclear capacity in return for lifting sanctions. Therefore, it is possible that China is eyeing other benefits of the deal in addition to its economic dimension.

For instance, this deal possibly allows China a potential foothold in the Middle East, a US dominated area of the world that is becoming increasingly vital to Beijing. About 40 percent of China’s energy needs are imported from the region. Thus, Beijing has significantly increased its economic, political and, to a certain degree, security footprint in the region in the past decade. China became the biggest trading partner and external investor for a significant number of Middle Eastern countries including Iran. Beijing currently participates in anti-piracy and maritime security missions in the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden and maintains a military base in Djibouti for such activities. Beijing has increased mediation efforts in crises in the region such as Syria and Yemen. China has conducted joint naval exercises with Iran on three occasions beginning in 2014. China’s energy needs push the country to have a greater presence in the Middle East. Iran is the only major oil rich country in the region not influenced by Washington, which presents an obvious opportunity for Beijing. The Sino-Iranian agreement could provide Beijing with a greater security role to protect its commerce and energy supply in Iran and the Persian Gulf. For example, access to the major Iranian port, Jask, gives Beijing a strategic vantage point in an area where most of the world’s oil transits and has been the strategic preoccupation of the US for decades. The US Navy’s fifth fleet is headquartered in the Kingdom of Bahrain, not far from the strait of Hormuz. China has constructed a series of ports along the Indian ocean creating refuelling and resupply stations from the South China sea to the Suez Canal. The ports are commercial in nature but also potentially have military value. For example, Beijing has access to ports in Sri Lanka and Pakistan which are widely considered to be potential foot holds for Chinese military presence.

Impact on relations with US

The pact could also have significant implications for Sino-American relations, potentially creating dangerous flashpoints within their deteriorating relations. The US’s 2018 National Security Strategy identifies China as an adversary and depicts the country as a “revisionist power”. On 23 July 2020 the US ordered the closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston, Texas. China retaliated by closing down a US consulate in south-western China. The US state department warned that China would be undermining its own stated goal of promoting stability and peace by defying US sanctions and doing business with Iran. The implementation of this deal could signal Beijing’s frustration with Washington. In 2018 the US started a trade war with China imposing sweeping tariffs on Chinese goods to which Beijing retaliated. The US started a major campaign against Huawei, a major Chinese telecommunications company, barring it from involvement from 5G development in the US. Washington also attempted, without much success, to persuade other countries follow suit. It is likely that Washington will further sanction Beijing if this agreement is implemented. It is also very likely that China will retaliate in like. Sino-American relations are likely to continue to sour over China’s deepening ties with Iran.

Has the South China Sea become a Flash point for conflict?

July 24, 2020 in UncategorizedThe South China Sea is developing into a perfect storm for potential conflict as an unwitting host of competing claims and counterclaims of ownership – involving China, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia – heightens the risk of a miscalculation, and military conflict. Couple that with America’s foreign policy of naval patrols and air reconnaissance missions in the disputed area, under the freedom of Navigation principle. As China and America play-out their rivalry and tensions in multiple arenas, amid the backdrop of China’s South-East Asian neighbours, wary of Beijing’s increasing assertion of its geo-political, military, economic, and diplomatic heft, there is little doubt that the South China Sea is a metaphor that brings it all to the boil.

Analysts have noted that in the grip of a global pandemic, China has sought to establish a dominant position in the area. In the last few months, Beijing has announced plans to carry out military drills in August that simulate the capture of the Dongsha Islands – which Taiwan currently controls. The New York Times also reports of allegations that China’s Coast Guard Vessel “rammed and sank” a Vietnamese fishing boat. Beijing has been accused of “stalking” a Malaysian oil vessel in waters belonging to Malaysia. The Philippines lodged a formal diplomatic compliant of a warship, purportedly Chinese, said to be pointing its radar system at a Philippine Naval Vessel. There have been reports of Chinese fishing boats turning-up in the Natuna Islands. This is an area that is internationally recognised as being part of Indonesia’s economic exclusive zone, but Chinese trawlers, backed by Chinese Coastal guard units, chase-out Indonesian fishers. The Chinese Foreign ministry sees the matter differently:

“Whether the Indonesian side accepts it or not, nothing will change the objective fact that China has rights and interests over the relevant waters,” is the official rejoinder.

Maps produced by China lay claim to large swathes of the South China Sea through its self-styled “Nine-Dash line”. An International Tribunal ruled in favour of the Philippines in its disputes over the Spratly Islands. The Arbitration Tribunal established that China’s “Nine-Dash Line” interpretation has no legality in international law. Beijing rejected the Tribunal’s ruling. That begs the question: of what significance are these waters? The South China Sea holds a strategic allure: first, as a vital shipping lane for global trade. It is estimated that one-third of global trade flows through these waters. The South China Sea is also reported to be rich in natural resources, including petroleum and gas, which crystalizes the geo-political tussle over its ownership.

“I think it’s fair to say we’re on the front line,” said Evan A. Laksmana, a senior researcher and military analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta. “If China feels it needs to provide some retribution of some kind, if we are seen as escalating, Southeast Asia would be looked at first.” There have been calls for ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia to beef up its military security in the face of not only China’s claim to 90 percent of the South China Sea, but its building of military bases and research stations on artificial reefs.

There is no doubt China holds considerable clout in South East Asia. Indonesia calls China its biggest trading partner. Philippines, under the leadership of Rodrigo Duterte has made the pivot from America to the embrace of China to benefit from its investments, trade, and further potential economic ties. The consequence of accommodating a Chinese economic hegemony, or call it the stick and carrot approach is what Professor Alexander Vuving of Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Honolulu means when he says: “The Chinese want to create a new normal in the South China Sea, where they are in charge, and to do that they’ve become more and more aggressive.”

America under President Trump has held a more hawkish China policy than recent US administrations and that has led to clashes over trade, telecoms giant Huwawei, Covid-19, and the security status of Hong Kong. The upshot is South East Asian countries, and China will be competing for strategic control of the South China Sea. For America, Beijing’s disputes with its neighbours offers the perfect context – for lack of a better description: to duke-out what many analysts have predicted will be the defining rivalry of the 21st century. It is quite ironic that there is scarcely any acceptable mechanism for arbitration to this geo-political powder keg involving naked display of might and ambition of a rising power, and a perfect excuse for intervention by an established one. I guess this script has déjà vu written all over it.